Myanmar Spring Chronicle – Scene of January 19

January 20, 2026

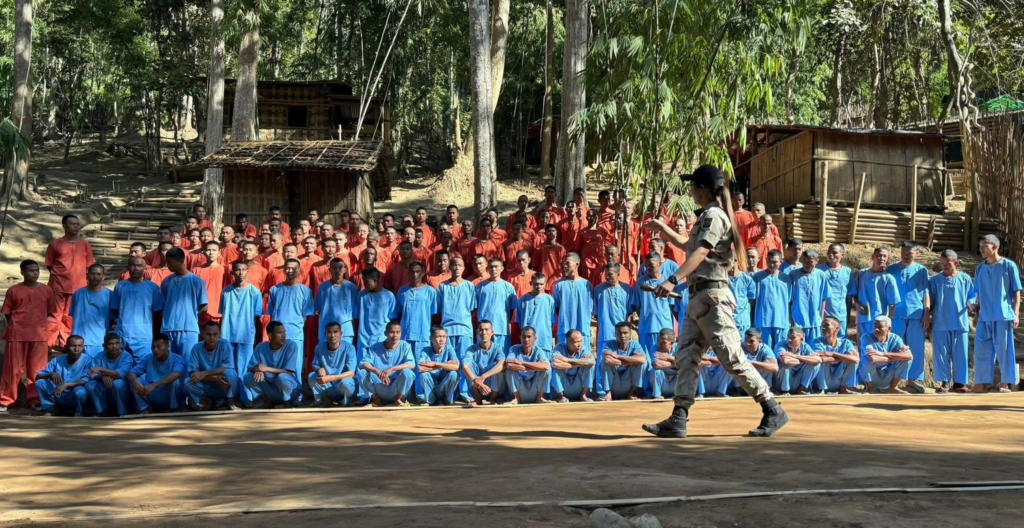

Nearly 80 detainees held as prisoners of war escape from Mae Sae (Karenni/Kayah State)

On the 18th of this month, an incident occurred in which prisoners of war held at the Mae Sae town prison in Karenni (Kayah) State—along with some medical personnel, including a medic and a number of medical assistants assigned inside the prison—escaped.

The day after the incident, further reports emerged that one of the escapees—said to be a prisoner of war and a Myanmar junta officer holding the rank of deputy lieutenant colonel—had reached Thailand’s Mae Hong Son Province along the Thai–Myanmar border and was arrested by Thai border security forces.

Mae Sae town lies close to the Thai border and has been under Karenni revolutionary forces’ control since around mid-2023, when they captured the town.

Last year, Karenni revolutionary forces attacked Hpasawng, which was under junta control, and by mid-year they reportedly seized two battalions based there—Light Infantry Battalion No. 134 and No. 135.

The prisoners of war who escaped from Mae Sae prison were reportedly junta officers captured in the Hpasawng battles, as well as in earlier battles in Bawlakhe prior to the Hpasawng fighting.

The statement said that nearly 80 people, including POWs and those assigned to provide medical care in the prison, escaped. During the escape, they allegedly seized nine firearms from prison security staff, tied up those staff, and left them inside the prison.

The Karenni State Interim Executive Council (IEC) issued the statement regarding this incident.

Karenni revolutionary armed groups have maintained that they detain POWs properly in accordance with international rules such as the Geneva Conventions, in stark contrast to the junta’s practices—where captured resistance fighters are reportedly tortured and killed.

Another possible factor is the resistance’s policy of encouraging enemy personnel—including officers—to join the CDM or to surrender during combat.

Under this approach, the resistance adopts a policy of not killing or torturing enemy personnel and uses channels that allow enemy troops to learn this, aiming to persuade more of them to defect or seek refuge with resistance forces—thereby weakening the junta’s military strength.

However, many people on social media argue that strictly observing international rules on the treatment of POWs is a “soft” or “naïve” approach. It is also widely noted that when resistance fighters are captured by junta forces, they are often killed on the spot rather than being detained and brought to court. In recent days, there was also an incident in a village in central Myanmar where a junta column reportedly raided a village where PDF members were resting, captured nine PDF fighters alive, and killed them.

Despite such behavior by the junta side, resistance armed forces say they continue to strictly follow international rules governing warfare.

At the same time, resistance forces often lack secure facilities, sufficient security personnel, and administrative experience in managing prisons and detention centers. For those reasons, escapes from detention sites and prisons have occurred from time to time.

After the launch of Operation 1027, during 2024 and 2025, resistance armed groups captured and detained thousands of junta personnel in battles. The MNDAA—despite having a ceasefire understanding with the junta—alone reportedly held thousands of prisoners, and even in recent days was seen transferring back hundreds of detainees to the junta.

It is not known what kinds of agreements or exchanges MNDAA may have negotiated with the junta in making such releases. Internationally, it is common to conduct prisoner exchanges in wartime; in Myanmar, prisoner swaps are not entirely absent, but they appear to be very rare.

One reason exchanges may remain limited could be that the junta side holds relatively few prisoners captured from resistance forces, reducing the possibility of reciprocal swaps.

Holding prisoners of war for months or years is undeniably a major burden for resistance armed groups. Over time, costs accumulate—food and supplies, shortages of security staff, and the long-term financial burden can become heavy.

Rather than maintaining long-term detention indefinitely, it may be more appropriate to pursue reciprocal exchanges for resistance members held by the junta, potentially through intermediary organizations such as the ICRC, by opening communication channels and negotiating practical arrangements.