Myanmar Spring Chronicle — December 12 Field Overview

December 13, 2025

Myanmar and the Expanding Crisis of Transnational Scam Syndicates Protected by Armed Groups

Over the past several years, the criminal networks known in Chinese as “pig-butchering” scams have grown from regional fraud operations into a global human-trafficking crisis. Citizens from dozens of countries have been deceived, extorted, trafficked, and in many cases enslaved under brutal conditions. Some have died. Behind these syndicates are not only criminal businessmen, but also armed groups who trade land, protection, and safe passage in exchange for profit.

From Myanmar’s borderlands to Cambodia’s semi-lawless enclaves, and to smaller pockets in Laos, Thailand, and the Philippines, these scam centers proliferated under the shadows of corruption, political complicity, and armed conflict. Among them, Myanmar emerged as the most notorious hub—not because the crime originated here, but because its fragmented territories, military alliances, and armed groups offered fertile ground for unprecedented expansion.

How Armed Groups Enabled a Criminal Empire

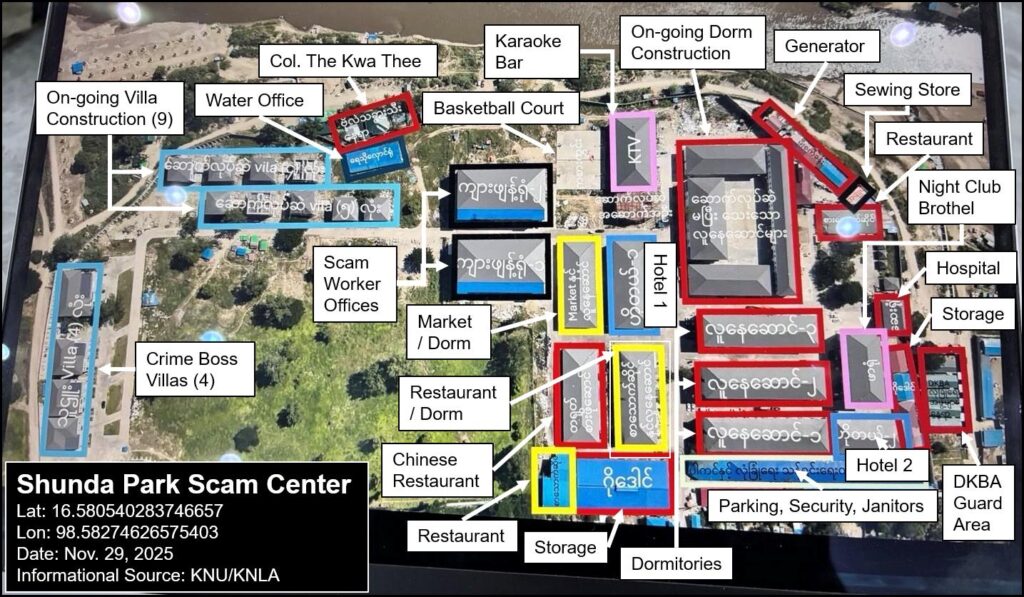

In Myanmar’s conflict zones, militia forces allied with the junta—such as the Border Guard Force (BGF) and the Kokang militia under Peng Daxun’s faction—actively ran and protected scam operations. Their involvement transformed northern Shan State, Myawaddy in Karen State, and parts of Mon State into vast scam enclaves between 2018 and 2024.

The Kokang-controlled areas, backed by the military, became a flagship example: a sprawling criminal economy operated for years under armed protection. Scam compounds later spread into UWSA- and SSPP-controlled zones, where torture, forced labor, trafficking of victims between syndicates, and even killings became routine.

Operation 1027 and the First Major Shock to the Scam Industry

When Operation 1027 erupted in late 2023, its goals were political and military. Yet anti-scam operations were included as an auxiliary objective, earning the quiet approval of China. Although the offensive was never primarily about law enforcement, it succeeded in destabilizing many scam centers in northern Shan State.

The collapse of these enclaves, however, did not end the problem. It merely shifted the industry southwards, toward the Myanmar–Thailand border. By 2024 and 2025, Myawaddy had become the new core of the scam world—thriving even as intense battles raged only kilometers away.

A Regional Web of Complicity

In these border zones, various actors formed an interlocking chain:

-

Chinese syndicate leaders who masterminded operations

-

Myanmar armed groups that provided land and security

-

Thai banks and financial channels used for money flows

-

Corrupt security and administrative officials on both sides of the border

-

Local politicians who turned profits into political power

This network ensured that even under military offensives and regional pressure, the scam industry continued to function and adapt.

Victims and Participants

Victims came from every continent—people deceived by online relationships or job offers, trafficked into compounds, and forced to work under threat of violence. Meanwhile, many local Myanmar residents joined the scam centers voluntarily, lured by wages unimaginable in any other local job. Because locals were seldom beaten as brutally as foreign victims, some began to view scam centers as mere “economic opportunities,” blurring the social perception of the industry itself.

2025: When the Crisis Became Global

By early 2025, the scale of the problem had surpassed regional boundaries. High-profile cases involving Chinese citizens induced China to intensify its pressure across Southeast Asia, triggering a wave of repatriations and relocations. Tens of thousands of foreign workers—both trafficked victims and voluntary participants—were sent back to more than fifty countries.

Myanmar’s junta, which controls almost none of the territories where the scam centers operate, adopted a strategy of denial:

-

claiming Myanmar does not financially benefit,

-

arguing that scam money does not enter the country’s banking system,

-

shifting blame to Thailand by asserting that 99% of trafficked arrivals crossed through Thai soil,

-

and accusing some foreign governments of misidentifying voluntary workers as trafficking victims.

The only visible involvement of junta authorities came during a limited handover of detainees to Thailand in Myawaddy.

Rising International Stakes

In Thailand, the scam crisis began to damage the country’s global reputation and tourism industry. International pressure—especially from China—pushed Thailand closer to confronting money-laundering networks and entrenched bribery that had shielded syndicates for years.

Meanwhile, the United States announced the creation of a Scamming Center Strike Force, signaling that major powers may increasingly treat scam syndicates not only as criminal enterprises, but as geopolitical leverage points.

This development has raised alarm in Myanmar and China. The concern is clear: the scam crisis may soon move from a law-enforcement challenge into the realm of strategic competition.

Conclusion

The pig-butchering scam phenomenon has evolved far beyond transnational crime. It now touches the political interests of great powers, the internal calculations of Myanmar’s military regime, and the regional dynamics of Southeast Asia. Both Myanmar’s junta and the Chinese government are beginning to confront a new reality:

a criminal industry once tolerated for profit is on the verge of becoming a geopolitical fault line.