Myanmar Spring Chronicle – November 10 Overview

(MoeMaKa, November 11, 2025)

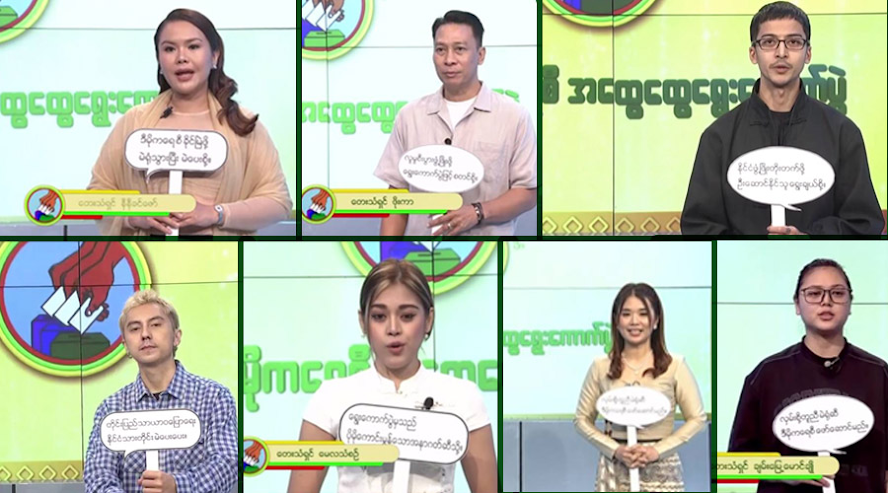

All Domestic Artists Pressured to Join the Junta’s Election Propaganda Campaign

For Myanmar artists living abroad — those who have left the country and not yet returned — there is little risk of being forced to participate in the junta’s campaign for the upcoming election. But for artists still living and working inside Myanmar, including singers, actors, and directors, resisting the junta’s pressure has become increasingly difficult.

Some actors, singers, and filmmakers have long-standing close ties with the military and willingly cooperate with it, so participation poses no problem for them. But for many other artists, being part of this propaganda effort is something they do not want at all.

Among them, some simply want to focus on their profession and stay away from politics, while others oppose the coup and dislike the military, yet cannot leave the country due to family or livelihood constraints. These artists find themselves trapped — facing intense pressure on all sides.

The first group includes pro-junta celebrities such as Khant Si Thu and Soe Myat Thuzar, who have worked closely with military-affiliated media. The third group includes those like Eiindra Kyaw Zin and Pyay Ti Oo, who were imprisoned after the coup for supporting the anti-dictatorship movement.

Throughout Myanmar’s modern history, the military has used art and literature as tools of propaganda. After independence, the military-run Myawaddy Magazine served as an official mouthpiece, and later in the Ne Win and BSPP eras, magazines like Ngwetaryi were taken over or censored. During the early post-independence years, military officers turned writers produced war-themed novels and films glorifying the Tatmadaw. By 1995, Myawaddy Television was launched, followed by the Myawaddy Daily newspaper after the 1988 coup — continuing the military’s long tradition of cultural propaganda.

Over the decades, government propaganda and military propaganda have been virtually identical — 70 to 80 percent overlapping. Today, under the coup regime, that overlap has grown to nearly 90 percent.

When the military seized power in 2021, many artists joined the anti-coup protests, supporting the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM). The junta retaliated by charging numerous actors and singers under Penal Code Section 505(a) and issuing arrest warrants. Many fled through border areas to neighboring or third countries; others were arrested and sentenced to long prison terms. Some spent years behind bars.

Meanwhile, those who remained neutral or did not join the protests faced social boycotts and online campaigns urging fans to “cancel” them for refusing to oppose the coup.

In the years following the coup, artists who performed at junta-organized events — such as Thingyan (Water Festival) celebrations — were also boycotted by the pro-revolution public.

Eventually, most artists chose to keep their distance from the regime, while a few pro-junta performers continued to appear alongside military leaders at official ceremonies and foreign visits, welcoming or entertaining them.

Now, as the junta prepares for the year-end election, it appears to have decided that every domestic artist must participate in promoting the event. The regime is reportedly producing propaganda short films, songs, and motivational videos to encourage public support — and artists are being pressured to take part.

Pro-revolutionary groups abroad — including exiled artists and activists — are calling for boycotts and social sanctions against any artist who joins the junta’s election propaganda.

Inside the country, however, the situation is dire: refusing to participate could mean arrest. Under such threats, very few artists dare to refuse. Some have even been detained simply for liking or sharing social media posts critical of the election. Fear among artists is clearly rising.

At the same time, the Spring Revolution movement’s call to boycott and condemn anyone participating in the junta’s campaign adds to the pressure. Many artists who privately oppose the regime find themselves caught in a no-win situation — fearing imprisonment if they refuse, but also public backlash if they comply.

The junta’s election propaganda drive is causing severe turmoil in Myanmar’s cultural sphere, widening the divide between artists and their audiences. It has blurred the lines between loyalty, survival, and moral choice — leaving the creative community fractured and uncertain about whether this moment represents irreparable division or the collapse of artistic unity altogether.