Than Win Hlaing

April 4, 2013

Gaunn-baunn is a Myanmar word of two syllables. Gaunn means “head” and baunn “wrap around.” Put together. It means a Myanmar head-dress, a length of thin fabric-silk or cotton, wrapped around the upper portion of the head as an ornamental covering.

In the days of the Myanmar monarchy, it used to be cherished by almost every Myanmar male from the king down to a lowly labourer as an ornamental head-dress.

Some say Myanma custom of wearing gaunn-baunn can be traced to India, where Muslims and Skihs, by long tradition, wear what the English-speaking people call turban (which can be etymologized as either from Turkish tulbant or Persian dulband.)

It was customary as early as in the days of Bagan period (11th to 13th century) for those serving under the Myanmar kings to wear guann-baunn every day of their service. There is a historical account of how Oak-hla-nge, son of Minister Raja-thin-gyan, unwrapped his gaunn-baunn and addressed the king Narapati formally, “I have the honor to have been serving under Your Majesty so faithfully and unremittingly that as Your Majesty may witness, my head has rotted and my hair near disintegrated.”

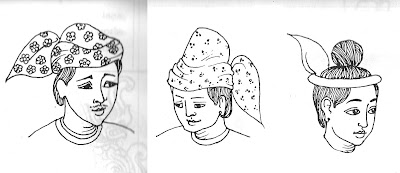

Myanmar males in the days of yore used to wear their hair long-long enough to knot their hair at the top of their heads, and the top-knot was called yaun. Ordinary civilians under Myanmar monarchy would wear their gaunn-baunn, covering their top-knots. However, Myanmar kings, male members of the royalty and courtiers would wrap their head-dresses round their heads, leaving their top-knots uncovered. Thus, their head-dresses were known as baunn or baunn-daw, baunn meaning “wrap” and daw an affix denoting royalty or power. The gaunn-baunn worn by ordinary civilians was called Oo-yit (Oo meaning “head” and yit “wind” or “wrap”).

Myanmar kings and male members of the royalty sported gold lame, ruby-studded, diamond-studded or emerald-studded head-dress, or baunn-daw studded with na-wa-rut (i.e the nine precious stones namely, ruby, pearl, coral, emerald, topaz, diamond, sapphire, garnet and cat’s eye), or head-dresses made of gold pieces beaten into gold leaf. Kings and crown prince’s would wear tightly rolled tinseled head-dresses round their heads, knotting at the back of their heads the opposite end-tips in such a way that only one tip would show pointing straight up (indicating their straightforwardness) while other male members of the royalty, ministers and court officials alike would wear theirs with the two end-tips pointing up at the back of their heads.

By the way, there’s a Myanmar proverb that uses Myanmar King’s upward pointing baunn-daw end-tip as a reminder to Ministers and court officials that they should always be alert to His Majesty’s whims and fancies. It goes, “baunn-daw ngeik seit-taw thi.” (See the gentle incline of the baunn-daw end-tip and know His Majesty’s whim).

Myanmar Kings so treasured their baunn-daw head-dresses that it was their custom to have baunn-daw saun (baunn-daw Hall) built directly in front of the main building of the palace, where his baunn-daw,crown and ma-gike (crested head-dress forming one of the ceremonial regalia of a monarch) were kept. The Hall also served as a resulting place for members of the Buddhist Order, ministers and racial chieftains before audience with the king.

The tightly rolled head-dress worn by ministers and high officials of the court, leaving their top-knots uncovered were called gaunn-baunn hpou, -lone (hpou. means “cork” and lone means “round”, which suggests that a length of cloth was tightly wrapped round the cork to make it into a gaunn-baunn), which you can, to this day, see an actor playing the role of a Minister wear in a traditional drama players on stage.

Towards the end of the Konebaung Dynasty (19th Century), there was marked increase in the use of foreign-made fabric for head-dresses by Myanmar princes and male citizens alike – especially silk fabric brought to Pathein by Arab merchants.

Round about that time, a head-dress known as kyay-taya gaunn-baunn (literally, “hundred birds head-dress” – using silk fabric with about hundred kinds of birds printed on it) was said to have young men of high society then. It even featured in the folk songs (sung to the long drum and the clash of cymbals) of the day, attesting to its popularity.

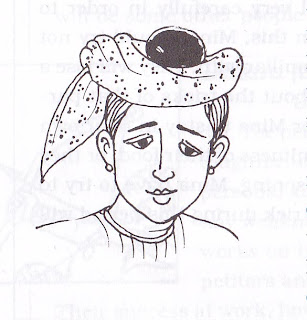

With the passage of time and the decreasing practice of sporting long hair and top-knots among Myanmar males, it becomes unnecessary for a gaunn-baunn to be wrapped around, leaving the top-knot uncovered. Meanwhile, cutting and cropping the hair Western-style became all the vogue among young generation. Thus, there came a practice of first putting on a skull-cap-like rat-tan-woven head-covering before wrapping it up with a length of fabric as gaunn-baunn this type of head-dress was then known as oak-paunn (oak meaning “cover” and paunn “wrap”).

With the upsurge of nationalism around 1922 when Yangon College was established, young Myanmar newly graduates attended their classes wearing gaunn-baunns of their own style, which somewhat resembled former wrap-around type of gaun-baun, (not using rattan-woven head-covering), and had an elongated triangular end-tip flying over the right ear. This style of head-dress was widely known as B.A gaunn-baunn.

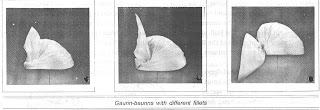

Present day Myanmar gaunn-baunn is more like a hat than a head-dress – coloured silk fabric glued onto a rattan-woven head-covering with a triangular end-tip hanging over the right sied. They are ready-made, and come in different sizes and colours. Thus, these days you don’t have to have the knack of wrapping it round your head anymore.

Myanmar’s racial brothers-the Shans, the Kachins, the Kayins, the Kayahs, the Chins and many others also wear head-dresses but the way they wear them, tugging or trailing the endtips are dissimilar-each peculiar to their respective race and custom.

A main feature of Myanmar culture, gaunn-baunn is always worn by Myanmar gentlemen on religious or public occasions. Prince Myingun is said to have always worn hin gaunn-baunn with a Western suit while he was in asylum abroad.

It is surprising to note that, unlike other aspects of Myanmar culture, the gaunn-baunn has wonderfully withstood the passage of so long a time and so many an era.

Translated by K.Z.W