>

ကမၻာ့သမုိင္းရဲ႕ သူရဲေကာင္း အမ်ဳိးသမီး ၁၆ ဦး

ဓာတ္ပုံသတင္း

မတ္ ၉၊ ၂၀၁၁

Time မဂၢဇင္းက ႏုိင္ငံတကာ အမ်ဳိးသမီးမ်ားေန႔ ႏွစ္ ၁၀၀ ျပည့္ေန႔ကုိ ဂုဏ္ျပဳရန္ ဓာတ္ပုံက႑တြင္ သူရဲေကာင္း အမ်ဳိးသမီး ၁၆ ဦး အေၾကာင္းကုိ တနလၤာေန႔က ေဖာ္ျပလုိက္သည္။

ယီမင္ႏုိင္ငံ ဒီမုိကေရစီအေရး လႈပ္ရွားမႈ ေခါင္းေဆာင္တဦးျဖစ္သူ Tawakul Karman

၏ ပုံကုိ ထိပ္ဆုံးတြင္ ေတြ႔ရသည္။

ေဒၚေအာင္ဆန္းစုၾကည္ကုိ ဒုတိယပုံတြင္ ေတြ႔ရသည္။

http://www.time.com/time/photogallery/0,29307,2057714,00.html မွ ကူးယူျပီး ေအာက္ပါအတုိင္း ေဖာ္ျပလုိက္ပါသည္။

|

Tawakul Karman, Yemen

Tawakul Karman, a 32-year-old mother of three and chair of Women Journalists Without Chains — a Yemeni group that defends human rights and freedom of expression — was filled with renewed energy watching the people of Tunisia and Egypt fight for democracy in January 2011. But her struggle to pressure Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh — who has been in power since 1978 — to step down began long before Tunisia’s revolution started a domino effect in the Arab world. Karman has been protesting in front of Sana’a University, in the nation’s capital, every Tuesday since 2007. She insists upon a peaceful approach to bring about change. Still, she has been arrested several times, including in late January, when protests broke out across Yemen, where 40% of the 23 million citizens live on $2 a day or less. Saleh has offered to resign once his term ends in 2013, but on March 4, he rejected a transition plan to democracy. Yemenis, including Karman, want change now. In February, Karman told TIME, “The goal is to change the regime by the slogan we learned from the Tunisian revolution: ‘The people want the regime to fall.’ ” —Frances Romero

|

|

Aung San Suu Kyi, Burma

After 15 long years under house arrest in Burma, Nobel Peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi was finally granted freedom in November 2010, even as her country and the cause she’s been fighting for sank deeper into political imprisonment under the military junta’s repressive rule. Known as “the Lady” to millions of Burmese citizens who consider her more of a goddess than a rebel, Suu Kyi has been the foremost leader in the effort to democratize the Southeast Asian nation as well as a courageous advocate for human rights and peaceful revolution. The daughter of an assassinated independence hero, Suu Kyi seemingly fell into her role as Burma’s icon. After spending much of her life overseas in India, the U.S., Japan and England, where she married and had two sons, Suu Kyi returned home in 1988 to care for her ailing mother. While there, protesters gathered to call for the ouster of a regime whose mismanagement had caused a sweeping economic downturn. The army fired on the assembled group of students, monks and workers, and for the first time, the Lady stepped forward to address the people. Suu Kyi founded the National League for Democracy in 1989, and the party secured a decisive victory in the 1990 elections, which would have effectively made Suu Kyi Prime Minister. Instead, the junta refused to hand over power and enacted a constitution that forbade Suu Kyi from ever serving as Burma’s leader. Despite this obstacle, the Lady and the Burmese people are not ready to give up. Since her release, Suu Kyi has sought to negotiate with the junta that imprisoned her for all those years, but so far it has ignored her. “I wish I could have tea with them every Saturday, a friendly tea,” the Lady told TIME after her release. And if not, “We could always try coffee.” —Erin Skarda

|

|

Corazon Aquino, the Philippines

A self-proclaimed “plain housewife,” Corazon Aquino led the Philippines’ 1986 “people power” revolution, toppling autocrat Ferdinand Marcos after 20 years of rule. Aquino’s journey from Senator’s wife to President of the Philippines began with the 1983 assassination of her husband Benigno Aquino Jr., who had returned from exile in the U.S. to run against Marcos. When the autocrat called a snap election, Corazon took up her husband’s cause. Though Marcos claimed electoral victory, Aquino led a peaceful revolution across the nation of impoverished islands. Emotional supporters came out in droves during a two-week standoff, and eventually, the military reversed course and supported her. Aquino became President upon Marcos’ resignation. Despite coup attempts and corruption charges, she took significant strides toward democracy, including ratifying a constitution that limits the power of the presidency. Long after stepping down in 1992, Aquino continued to advocate against policies she felt threatened the country’s democratic ideals. Though she died in 2009, Aquino remains a symbol of the power of peaceful popular movements. —Zoe Fox |

|

Phoolan Devi, India

Phoolan Devi, the “Bandit Queen,” is remembered as both a champion of India’s poor and one of the modern nation’s most infamous outlaws. Following an early, nonconsensual marriage and several sexual abductions, Devi began a streak of violent robberies across northern and central India, targeting upper castes. In 1981 she led her gang of bandits to massacre more than 20 men in the high-caste village where her former lover was killed. Devi negotiated her sentence with the Indian government to 11 years in jail. Within two years of her release, she was elected to Parliament. While some say she did little to improve the lower castes’ plight during her two terms in office, her opposition to the caste system made Devi a symbol for the rights of the poor and the oppressed. —Zoe Fox

|

|

Angela Davis, the U.S.

By the time Angela Davis was 26, she was a scholar, a political activist and a Most Wanted Fugitive of the FBI. Her roots as a leader during the political turmoil of the 1960s stretch back to her childhood in segregated Birmingham, Ala. After spending a year at the Sorbonne, Davis returned to a racially heated America. By the late ’60s, she held membership in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Black Panther Party and the American Communist Party. Her militant involvement cost her a UCLA lecturer position when the California regents learned of her affiliations in 1970. However, Davis’ activism continued with her support of three Black Panther inmates at Soledad State Prison. At their trial, for a prison guard’s murder, a botched kidnap and escape attempt resulted in the death of a federal judge, Harold J. Haley. Davis was accused of supplying the guns. She fled, sparking a furious manhunt and landing her a spot on the Most Wanted list. While she was on the run, a movement advocating her freedom flourished. Davis was caught in New York but was acquitted in 1972. Despite the agitation of then California Governor Ronald Reagan, she resumed her teaching career at several universities in the state and is now a professor emerita at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She has authored several books, including Women, Culture and Politics (1988) and Are Prisons Obsolete? (2003). —Madison Gray

|

|

Golda Meir, Israel

David Ben-Gurion famously described Golda Meir as “the only man” in his Cabinet. Although best known as Israel’s Prime Minister during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Meir made her mark on the revolutionary Zionist movement during the pre-state period. After several influential Zionist leaders were arrested in 1946 in Palestine, Meir became the primary negotiator between the Jews and the British Mandate. Simultaneously, she stayed in close contact with the armed Jewish resistance movements. When the Arabs rejected the U.N.’s 1947 recommended partition of Palestine, Meir ensured that the young Jewish settlement would not be defeated in the imminent war. During a January 1948 trip to the U.S., she raised $50 million from the Jewish diaspora community. Ben-Gurion said Meir would be remembered as “the woman who got the money to make the state possible.” That spring, she was one of the 25 signers of Israel’s Declaration of Independence. —Zoe Fox

|

|

Vilma Lucila Espín, Cuba

Many of the leaders of the Cuban revolution were among the very Latin elites whose supremacy over the masses they set out to topple — i.e., they were male and from the professional class. Fidel Castro was trained as a lawyer, while Ernesto “Che” Guevara studied medicine. But the spirit of the rebellion was most vividly embodied by the “First Lady” of Cuba’s communist revolution, Vilma Lucila Espín. Her father was a lawyer for the rum company Bacardi, whose business exploits in Cuba were viewed by Castro’s July 26 Movement as treating the island nation like a Yankee playground. After training as a chemical engineer, including a year of study at MIT, Espín took up arms against the Batista dictatorship in the 1950s and debunked the notion of the docile Caribbean woman with her public appearances in full army fatigues. —Daniel Fastenberg

|

|

Janet Jagan, Guyana

For Chicago-born Janet Jagan, the vibrant labor struggles in the mid-20th century of her own country were not enough. After falling in love with Cheddi Jagan, a Guyanese dentistry student at Northwestern, Jagan followed her future husband, with Lenin’s writings in hand, to his homeland in 1943. Setting up shop as a dental assistant, she set out on a path that would lead to her becoming Guyana’s first female President. In 1946 she and her husband founded the People’s Progressive Party, which sought to promote Marxist ideals as well as decolonization from the U.K. In the late 1940s, the Jagans inspired strikes by domestic workers in what was then referred to as “British Guyana.” The movement attracted the ire of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who put the Jagans in jail. But Janet Jagan proved to be a political survivor, remaining in the game despite various attempts to purge her from leadership posts. An impolitic p.r. campaign singing the praises of the Cuban revolution in the 1960s attracted the attention of John F. Kennedy, who in turn targeted Guyana’s labor unions. Relegated to the sidelines after a leftist government flopped in the 1960s, Jagan took to the pages of the Mirror

newspaper, becoming its editor. By the time she was elected President in 1997, the country had achieved the independence from Britain that she had sought and had nationalized much of its economy. —Daniel Fastenberg

|

|

Jiang Qing, China

Looking back, it’s almost as if Jiang Qing lived two lives: one that began in extreme poverty and led to a short career as an actress and several failed marriages, and another as a radical member of the communist regime, which brought terror and destruction to China during the Cultural Revolution. But despite the duality of her life, Jiang is remembered as one of the most brutal, unrepentant revolutionaries in modern history. After marrying Chairman Mao Zedong in 1938, Jiang used her status to satisfy her unyielding desire for power. “The Madame,” as she was known, managed to climb the ladder of the Communist Party, eventually becoming the leader of the infamous Gang of Four — a group that included Zhang Chunqiao, Yao Wenyuan and Wang Hongwen and was thought to be responsible for much of the persecution and destruction that took place from 1966 to 1969. Exact death tolls during this time are unknown, but estimates place them at 500,000, in addition to the destruction of countless cultural entities such as ancient books, buildings and paintings. While Jiang was heavily involved in the Cultural Revolution, she was quick to assign responsibility to Mao, famously saying, “I was Mao’s dog; I bit whom he said to bite.” Jiang refused to apologize for the criminal charges that were eventually brought against her, instead spending a decade in prison before allegedly committing suicide in 1991. —Erin Skarda

|

|

Nadezhda Krupskaya, Russia

The spirit of protest coursed through Nadezhda Krupskaya’s veins early in life. As a girl in late-19th century St. Petersburg, she would play with children outside of the factory where her father worked and ambush the manager with snowballs. Educated at a liberal high school, Krupskaya went on to teach evening classes to industrial workers, and by 1889, she had encountered Marxism in underground circles. Along with fellow radical Vladimir Lenin, she helped set up the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class in 1895. Police arrested them both shortly afterward, and they married while exiled in Siberia. After her release in 1901, she followed Lenin to Munich, Geneva and London, all the while helping run Iskra

(the Spark), an international newspaper for Marxists. After World War I, Krupskaya returned to Russia and became a key figure in the Bolshevik Party in Vyborg — a major working-class hub in Petrograd — and pressed the central committee to kick-start the October Revolution in 1917. Her ashes are interred in the Kremlin Wall adjacent to Lenin’s Mausoleum in Red Square. —William Lee Adams |

|

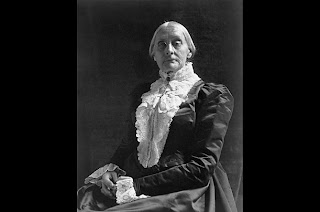

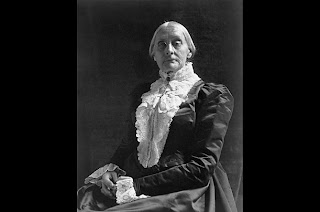

Susan B. Anthony, the U.S.

A male schoolteacher once told young Susan B. Anthony that she didn’t need to learn long division because “a girl needs to know how to read the Bible and count her egg money, nothing more.” She never forgot the slight. In 1846 Anthony, then a 26-year-old school headmistress, began campaigning for equal pay for female teachers. Five years later, she met fellow women’s-rights advocate Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the outspoken duo began touring the country arguing the case for women’s suffrage. In 1868 Anthony first published The Revolution, a women’s-rights newspaper, and a year later she founded the National Woman’s Suffrage Association. Plenty of men tried to stop her along the way. U.S. marshals arrested Anthony for voting illegally in the 1872 presidential election, and a judge later fined her $100. “I shall never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty,” she said at the time. Anthony died in 1906 — 14 years before the 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote. —William Lee Adams

|

|

Emmeline Pankhurst, Britain

No one embodied the expression “Well-behaved women rarely make history” quite like Emmeline Pankhurst. As the leader of Britain’s women’s-suffrage movement, Pankhurst was not only a pioneer of women’s rights in the U.K. but also a staunch advocate of public revolt. Encouraged by her father, Pankhurst’s interest in the suffrage movement began at a young age. At 20 she wed Richard Pankhurst, a lawyer who encouraged her endeavors with the Women’s Franchise League. After her husband’s death in 1898, Pankhurst’s involvement with the suffrage movement deepened, and she formed the Women’s Social and Political Union, which embraced the motto “Deeds, not words.” The WSPU, led by Pankhurst and her eldest daughter Christabel, carried out public demonstrations and did not shy away from violent activism — arson, vandalism and hunger strikes were commonplace for the group. Pankhurst was routinely arrested — in 1912 alone she was arrested 12 times — but she never strayed from her pursuit of equality. She reminded the courts in 1912 that “we are here not because we are lawbreakers; we are here in our efforts to become lawmakers.” While the merits of her methods are still debated today, there is no doubt over the role that Pankhurst played in the enfranchisement of British women. The right was extended to all women in 1928, the year Pankhurst died. —Megan Gibson

|

|

Harriet Tubman, the U.S.

Explaining her decision to escape from slavery, Harriet Tubman once quoted an earlier American revolutionary by saying, “There was one of two things I had a right to, liberty or death; if I could not have one, I would have the other.” Choosing liberty, Tubman, who was born a slave in 1820, fled Maryland and followed the North Star to the free state of Pennsylvania. A year later, she returned to Maryland to help her family escape, the first of 19 missions she would make to rescue more than 300 slaves on the Underground Railroad. After an 1850 law required free states to return escaped slaves to their owners, Tubman made sure slaves could escape even farther north, to Canada. During the Civil War, she was the first woman to lead a military expedition, liberating more than 700 slaves in South Carolina. Tubman ended her life of activism fighting for women’s suffrage in New York. —Zoe Fox

|

|

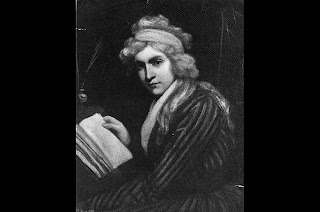

Mary Wollstonecraft, Britain

In the male-dominated, hierarchical society of 18th century Britain, Mary Wollstonecraft was a radical who publicly put forward the unprecedented claim that women were more than possessions. She went head to head with one of the most prominent political thinkers of the time, Edmund Burke. And in her two most famous works, A Vindication of the Rights of MenA Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1791), she demonstrates a strong political voice, defending the rights of women as equal to those of men. In Wollstonecraft’s opinion, the way in which girls were brought up, to be “empty-headed play things,” contributed to a morally bankrupt society, ungoverned by reason. It was in this view of the world that Wollstonecraft showed her true colors as one of the earliest and most influential rebellious women. —Elizabeth Tyler

(1790) and |

|

Joan of Arc, France

The French peasant girl had a dream — in fact she had many dreams, visions in which Christian saints would come to her, urging her to take up the fight against the English, who occupied much of northern France. Improbably, Joan made her way to the court of the cowed French dauphin, or prince, and impressed the royals with her holy cause to the point that she was given armor and troops to command. At Orleans in 1429, Joan proved her mettle by famously leading the assault that lifted the English siege of the city. A pivotal victory, it spurred other quick successes and turned the tide against the English invaders. A few years later, though, Joan was captured by the forces of England’s French allies and burned in a public square on grounds of heresy and witchcraft. The French King Charles VII, whose crown had been secured in part by Joan’s heroics, did little to try to save her. But history and popular legend redeemed Joan, who was canonized in 1920 by the Vatican and remains one of France’s patron saints. —Ishaan Tharoor

|

|

Boudica, Britain

In the 1st century A.D., a native rebellion shook a backward, remote corner of the Roman Empire: Britain. At its head was an angry woman, Boudica, Queen of the Iceni, a tribe that dwelled in what is now eastern England. The Iceni had been a peaceful folk, content under the Pax Romana. But after Boudica’s husband died, an avaricious Roman official annexed her lands and had Boudica publicly flogged and her daughters raped. Not long thereafter, with the Romans distracted on a campaign in Wales, Boudica rose up, leading a coalition of tribes on a revenge mission, surprising Roman garrisons, razing cities to the ground (including ancient London) and slaughtering tens of thousands of Romanized Britons. The uprising prompted some in Rome to consider a full withdrawal from the troublesome island colony, but the better-equipped and trained Roman forces eventually defeated Boudica’s rebels. According to some accounts, much like Cleopatra, Boudica took her own life rather than risk capture. She is remembered as one of Britain’s original nationalist heroes, a righteous, vengeful mother of the land. In the 19th century, Queen Victoria invoked the spirit of Boudica to characterize her own reign, presiding, at the time, over the world’s great superpower. —Ishaan Tharoor |